Benefits of nylon and zinc

A recent study by the Hohenstein Institute highlights the risks of nicotine transfer from clothing. The term ‘third-hand smoke’, coined by Hohenstein scientists, refers to that part of cigarette smoke which is not inhaled by either the smoker themselves or by passive smokers, but is deposited on surfaces, cushions, carpets, curtains or clothing. There, scientists say, the concentrations of toxic substances from cigarettes are far higher than in smoky air, an

30th September 2010

Innovation in Textiles

|

Bönnigheim

A recent study by the Hohenstein Institute highlights the risks of nicotine transfer from clothing. The term ‘third-hand smoke’, coined by Hohenstein scientists, refers to that part of cigarette smoke which is not inhaled by either the smoker themselves or by passive smokers, but is deposited on surfaces, cushions, carpets, curtains or clothing.

A recent study by the Hohenstein Institute highlights the risks of nicotine transfer from clothing. The term ‘third-hand smoke’, coined by Hohenstein scientists, refers to that part of cigarette smoke which is not inhaled by either the smoker themselves or by passive smokers, but is deposited on surfaces, cushions, carpets, curtains or clothing.

There, scientists say, the concentrations of toxic substances from cigarettes are far higher than in smoky air, and they can be released again, for example by contact with the skin. In fact, only about 30% of the smoke is inhaled, scientists say.

“The remaining 70% go out into the atmosphere and form a reservoir of ‘third-hand smoke’.” This is why scientists at the Institute for Hygiene and Biotechnology (IHB) at the Hohenstein Institute studied the question of whether and to what extent ‘third-hand smoke’, in the form of the toxic substances on clothing, could damage the health of infants.

Unlike with passive smoking, where the risks of inhaled nicotine, which is toxic to the nervous system, are well-known, the first question in connection with ‘third-hand smoke’ was to examine whether there are other health risks if the transmission channel is the skin. So researchers at the Hohenstein Institute wanted to find out exactly what happens when parents have a smoke outside on the balcony and then, after their break, take their baby in their arms again.

To find the answer, the scientists at the IHB used a specially developed cell culture model of baby skin - a 3D skin model, the cell composition, structure and properties of which imitate the skin of babies and toddlers.

To simulate the effects of third hand smoke, a T-shirt was deliberately impregnated with nicotine, the main toxic ingredient of cigarettes, just like during a smoker's break on the balcony. So that the quantity of the toxin could be verified afterwards, radioactively marked nicotine was used. Then the smoke impregnated textiles were placed on the baby skin and the penetration of the nicotine into the skin was tracked in tracer studies.

The results produced by the Hohenstein scientists showed for the first time that the neurotoxin nicotine is not only released from clothing by perspiration so that it can be detected in all the layers of baby skin, but it is also transported through the skin into deeper tissue layers.

The results produced by the Hohenstein scientists showed for the first time that the neurotoxin nicotine is not only released from clothing by perspiration so that it can be detected in all the layers of baby skin, but it is also transported through the skin into deeper tissue layers.

For comparison, the scientists repeated the experiments using donor skin from adults, and found that the results were the same.

So do the nicotine and other toxins from the smoke that have penetrated the skin have any verifiable harmful effects on the body, long after the last cigarette has been put out?

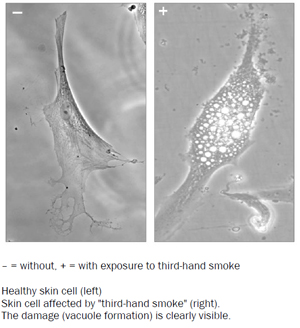

To answer this question, the researchers at the IHB again exposed textiles to a specific amount of cigarette smoke. Then they investigated whether toxins could be released from the textile by perspiration and how cultures of skin and nerve cells react to the mixture of smoke and sweat. Here again the results were unambiguous: in the laboratory experiment, scientists say the toxins from the cigarette smoke that were dissolved in the perspiration caused massive damage to the skin cells; for example, they changed their shape and even, where the concentration was high, died off.

Similarly, nerve cells, which are particularly active during the early stages of development, showed clear changes and were no longer able to connect properly with one another. The Hohenstein scientists are now publishing the results of their work in a scientific journal.

"Parents should be aware", says Prof. Dirk Höfer, Director of the Institute for Hygiene and Biotechnology at the Hohenstein Institute, "that their own clothing can transmit toxins from cigarette smoke.” The Hohenstein scientists are now working hard to find a solution for this problem.

Prof. Höfer says: "We are currently looking at textile coatings which could neutralise the toxins from the cigarette smoke and so reduce the danger of ‘third-hand smoke’. But we still need to do more research." However, by working with skilled partners in industry, it is possible that they may achieve this goal quite soon. Especially for developing baby-friendly clothing to be worn next to the skin, the "baby skin model" used by the Hohenstein scientists now offers a versatile measuring system.

Contact address for more information: Dr. Timo Hammer, Institute for Hygiene and Biotechnology at the Hohenstein Institute, email: [email protected]

Business intelligence for the fibre, textiles and apparel industries: technologies, innovations, markets, investments, trade policy, sourcing, strategy...

Find out more