Exploring routes to self healing

Statistical modelling demonstrates that perpetual repair is possible.

28th January 2026

Innovation in Textiles

|

USA

Researchers in North Carolina and Houston have created a self-healing composite that is tougher than materials currently used in aircraft wings and turbine blades and can repair itself more than 1,000 times.

It is estimated that this self-healing can extend the lifetime of conventional fibre-reinforced composite materials by centuries compared to the current decades-long design-life.

“This would significantly drive down the costs and labour associated with replacing damaged composite components and reduce the amount of energy consumed and waste produced by many industrial sectors because they’ll have fewer broken parts to manually inspect, repair or throw away,” says Jason Patrick, associate professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at NCSU.

Fibre-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites consist of layers of fibres such as glass or carbon that are bonded together by a polymer matrix, often epoxy. The self-healing technique developed by the researchers targets interlaminar delamination, which occurs when cracks within the composite form and cause the fibre layers to separate from the matrix.

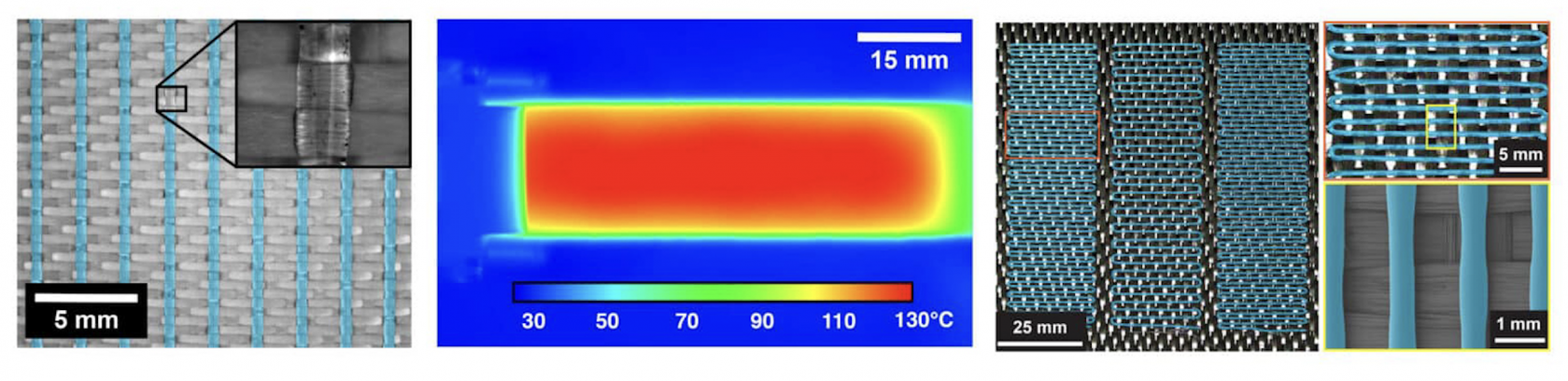

The self-healing material resembles conventional FRP composites, but with two additional features. Firstly, the researchers 3D-print a thermoplastic healing agent onto the fibre reinforcement, creating a polymer-patterned interlayer that makes the laminate two to four times more resistant to delamination. Secondly, they embed thin, carbon-based heater layers into the material that warm up when an electrical current is applied. The heat melts the healing agent, which then flows into cracks and microfractures and re-bonds delaminated interfaces, restoring structural performance.

1,000 cycles

To evaluate long-term healing performance, the team built an automated testing system that repeatedly applied tensile force to an FRP composite producing a 50 millimetre-long delamination, then triggered thermal remending. The experimental setup ran 1,000 fracture-and-heal cycles continuously over 40 days, measuring resistance to delamination after each repair.

“We found the fracture resistance of the self-healing material starts out well above unmodified composites,” says Jack Turicek, a graduate student at NC State. “Because our composite starts off significantly tougher than conventional composites, this self-healing material resists cracking better than the laminated composites currently out there for at least 500 cycles. And while its interlaminar toughness does decline after repeated healing, it does so very slowly.”

In real-world scenarios, healing would only be triggered after the material is damaged by hail, bird strikes or other events, or during scheduled maintenance. The researchers estimate the material could last 125 years with quarterly healing.

“This provides obvious value for large-scale and expensive technologies such as aircraft and wind turbines,” Patrick says. “But it could be exceptionally important for technologies such as spacecraft, which operate in largely inaccessible environments that would be difficult or impossible to repair via conventional methods on-site.”

The study also shed light on why recovery slowly declines over time. With continued cycling, the brittle reinforcing fibres progressively fracture, creating micro-debris that limits rebonding sites. In addition, chemical reactions where the healing agent interfaces with the fibres and polymer matrix decline over time. Even so, modeling suggests the self-healing will remain viable over extremely long time scales.

“Despite the inherent chemo-physical mechanisms that slowly reduce healing efficacy, we have predicted that perpetual repair is possible through statistical modelling that is well suited for capturing such phenomena,” says Kalyana Nakshatrala, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Houston.

Patrick has patented and licensed the technology through his startup company, Structeryx.

Business intelligence for the fibre, textiles and apparel industries: technologies, innovations, markets, investments, trade policy, sourcing, strategy...

Find out more